In this page

When to use scripting?

What is Groovy?

How can I learn Groovy?

Advanced script examples

Recommended tools

Writing Groovy scripts

Your first script in 2 minutes

Executing scripts efficiently with executeOnce()

Passing objects from templates to scripts

Passing objects from scripts to templates

Scripting good practices

Practical scripting

Unit testing

Running the unit tests in the IDE

Running the unit tests in Jira

Debugging

Debugging in the PDF template

Debugging in the IDE

Debugging in Jira

Logging

Logging from scripts

Further reads

Recipes

Troubleshooting

Next step

Why scripting?

Better PDF Exporter uses Velocity as its language to define PDF document templates. In the templates, Velocity logic statements are mixed with FO formatting tags to get the final result. Although these tools are powerful at what they do, it is still purely a template language, not a full-blown programming language. That may impose limitations when implementing more complex PDF document exports.

In many cases, this limitation is not a real problem, as your PDF document exports may not require any complex logic. You just want to display field values, do some formatting, make trivial if-then switches. To implement these, using Velocity alone is sufficient, and you should not complicate your life with scripting.

In other situations, the requirements for the logic that needs to be built into your templates are more complex. To implement these, Velocity alone may not be enough, you will need to do some scripting.

Don't worry, scripting is easy and it opens new horizons for your PDF documents!

When to use scripting?

Some use case examples that you can implement only with scripting (not in Velocity alone):

- Draw charts. (Example: generate graphical visualization in project status reports.)

- Integrate with external resources. (Example: integrate vendor information into your quotes queried from an external CRM database or an external webservice.)

- Do precise arithmetic. (Example: calculate precise money values in invoice documents.)

- Access Jira internals. (Example: execute a secondary saved filter to collect more data.)

- Implement data processing algorithms using advanced data structures. (Example: build dependency tables for traceability matrixes.)

What is Groovy?

Groovy is the scripting language used by the Better PDF Exporter for Jira app. In a wider scope, Groovy is the de-facto standard scripting language for the Java platform (the platform on which Jira itself runs).

What are the advantages of Groovy compared to other scripting languages?

- It is very easy to learn and use.

- It is already known for Jira users, as several other Jira apps use Groovy to implement custom logic.

- It beautifully integrates with Jira internals.

- There are lots of sample code, documentation and answers available on the web.

- It is mature and proven, having been used in mission-critical apps at large organizations for years.

How can I learn Groovy?

The basics of Groovy can be learnt in hours, assuming that you have some background in a modern programming language like Java, Javascript or Python.

Useful resources:

- Groovy: Getting Started

- Groovy documentation

- The book Groovy in Action is well worth the read, if you prefer paper-based formats.

- Groovy 2 Cookbook shows the solution for typical use cases, like connecting to databases, working with regexp's.

- Stack Overflow has a lots of answers for Groovy related questions.

Advanced script examples

Better PDF Exporter for Jira is shipped with a large selection of default PDF templates and Groovy scripts. Looking into those is the absolute best way to learn more about real-life implementations. Even if a template is not perfectly matching your use case, study it for ideas and good practices!

Recommended tools

If you don't plan to make major changes, you can do all your work in the app's built-in editor.

If you look for more, try these:

- If you don't want to install anything, these websites allow editing and executing Groovy:

-

Or, you can install these full-blown IDEs:

- IntelliJ IDEA supports working with Groovy scripts.

- IntelliJ IDEA supports working with Velocity templates.

- Eclipse IDE with the Groovy-Eclipse extension supports working with Groovy scripts (*.groovy).

- Eclipse IDE with the Velocity UI extension supports working with Velocity templates (*.vm).

Writing Groovy scripts

Your first script in 2 minutes

Here is the good old Hello world! program implemented in Groovy for the Better PDF Exporter for Jira appp.

First, save your logic to a Groovy script file hello-world.groovy:

// hello-world.groovy

helloWorld = new HelloWorldTool()

class HelloWorldTool {

def say() {

"Hello world!"

}

}

Then, execute this in your template hello-world-fo.vm:

## hello-world-fo.vm

## execute the script with the $scripting tool

$scripting.execute("hello-world.groovy")

## after executing the script, the object created by the script is available as "$helloWorld"

## let's call a method and put the greeting text to a text block!

<fo:block><fo:inline font-weight="bold">Ex 1:</fo:inline> $helloWorld.say()</fo:block>

Tadaam! That's it. Now you have the text generated by the Groovy code in the PDF.

Tip: it is usually a good idea to follow the naming convention used above. If your template is an implementation of "my document type", then save the template to my-document-type-fo.vm and the script to my-document-type.groovy. It helps to see what files belong together.

Executing scripts efficiently with executeOnce()

(since Better PDF Exporter for Jira Cloud 4.2.0)In addition to execute(), the scripting tool offers another method intuitively called executeOnce(). This second method guarantees that if the same script (identified by its filename) was passed to it multiple times, that will be executed only for the first time. All further method calls during the same PDF file rendering will immediately return.

See this example to understand the difference:

$scripting.execute("foo.groovy")

$scripting.execute("foo.groovy") ## executed for the second time

$scripting.execute("foo.groovy") ## executed for the third time

$scripting.executeOnce("bar.groovy")

$scripting.executeOnce("bar.groovy") ## not executed

$scripting.executeOnce("bar.groovy") ## not executed

Okay, why should you use it?

It's all about being efficient and about keeping the template code organized and simple.

Executing scripts takes time. Although it is rather fast (around 100 milliseconds for most scripts shipped with the app), we want to execute scripts only when it is absolutely necessary. Plus, we want to make the execution as efficient as possible without complicating the Velocity template.

To achieve this, we follow this pattern (which was also used by the "Hello world" example above):

- We run the script in a late moment when we are 100% sure that it is necessary.

- We run the script only once.

- During that single execution, the Groovy script defines a class which implements the custom logic, and instantiates one object of that class.

- There is only one object instance required, which is made available for the Velocity template.

The executeOnce() helps us with the first and the second points. We don't need to check if the script was already executed in the Velocity code using flags. We can just call executeOnce() method any time, and it guarantees that the execution is not redundant.

Passing objects from templates to scripts

After the script execution basics, the next step is to learn how to share information between PDF templates and scripts.

When you execute a script, the following happens under the hood:

- The class generator will convert the script to an actual Groovy class. (The script hello-world.groovy will be converted to the class named "hello-world" in the background.)

- The class generator will convert the Velocity context objects to properties of the generated class.

- Because the generated class is the "outermost" class, its properties appear like "global variables" in the script. Consequently, scripts can access all the Velocity context objects through global variables! (More on "global" a bit later).

Simple, right?

Here is a concrete example. You probably know that the currently signed-in Jira user is available as $user in the PDF template. At the same time, this is also available as the object user in Groovy!

// hello-world.groovy

// "user" is available from the Velocity context

// we are injecting it to HelloUserTool through its constructor

helloUser = new HelloUserTool(user)

class HelloUserTool {

def user

HelloUserTool(user) {

this.user = user // store the argument for later use

}

def say() {

"Hello ${user.displayName}!" // use a property

}

def say2(issues) {

"Hello ${user.displayName}! You have ${issues.size()} issues." // use a property and a method argument

}

}

Let's greet him:

## hello-world-fo.vm <fo:block><fo:inline font-weight="bold">Ex 2:</fo:inline> $helloUser.say()</fo:block>

You can easily pass arguments to the Groovy methods:

## hello-world-fo.vm <fo:block><fo:inline font-weight="bold">Ex 3:</fo:inline> $helloUser.say2($issues)</fo:block>

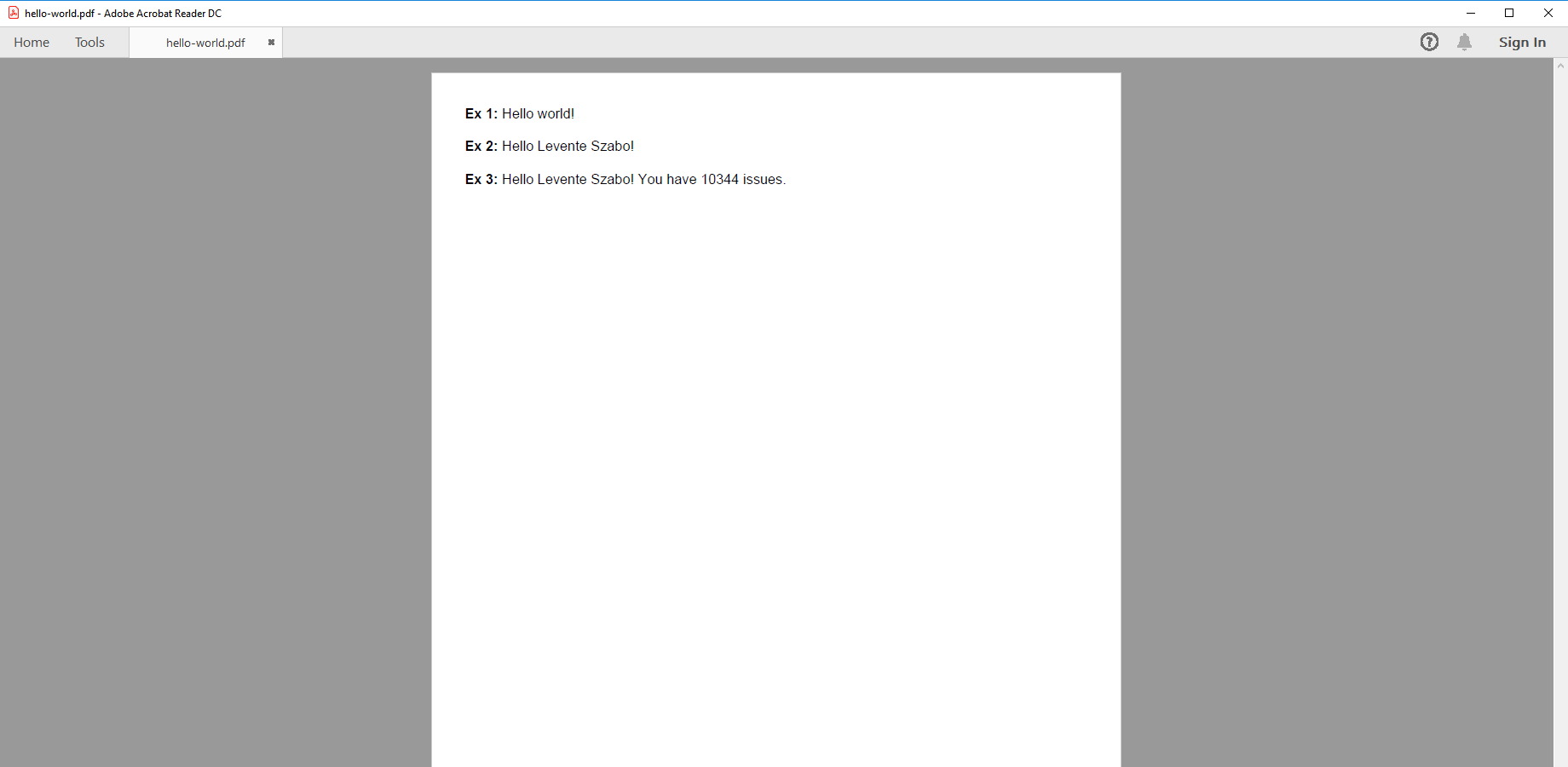

The resulted PDF:

Note: although from the above code it may feel like as if we had a global variable "user", this is not true. In fact, there is no such thing like "global" in Groovy! Read this article to avoid surprises.

Passing objects from scripts to templates

The rule is simple: all so-called "binding variables" created in Groovy will be automatically available in the PDF templates.

What is a binding variable? When a variable is not defined in the script, it is in the binding.

Consequently, Groovy variables that are not defined in the script will be available in PDF templates:

// will be available in the template: bindingVariable = "I am a binding variable" // will *not* be available in the template: String localVariable = "I am a local variable"

Therefore, we recommend the following simple convention:

- Implement your logic in a lightweight Groovy class.

- Create an instance of this class as a binding variable.

- To access Groovy calculated information in the PDF template just call the methods of this instance.

Scripting good practices

- Separation of concerns: clearly separate visuals and logic. Use Velocity for iterating, trivial if-then's, formatting, and use Groovy for implementing complex logic. Not vice versa!

- Follow the naming conventions suggested in this article: call your tool class FooBarTool and instantiate it with the name fooBar.

Practical scripting

Unit testing

Writing unit tests for your Groovy scripts is a great way to achieve quality and reliability. It can also be a technique to work faster when writing more complicated scripts.

For practical reasons, we recommend packaging your unit tests together with the tested Groovy class unless the resulted script grows inconveniently large.

Here is a Groovy tool sample that counts the resolved issues in the input collection plus the corresponding unit test:

resolvedCounter = new ResolvedCounterTool()

public class ResolvedCounterTool {

long getResolvedCount(issues) { // <- the tested logic

Closure query = { it.resolutionDate != null }

return issues.findAll(query).size()

}

void testGetResolvedCount() { // <- the unit test

def issues = [ [:], [ resolutionDate: new Date() ], [:] ] as Set // mock issues

def result = getResolvedCount(issues)

assert result == 1

}

}

Running the unit tests in the IDE

Now, bring the previous script to your favorite IDE and add these lines to the end of the script:

resolvedCounter = new ResolvedCounterTool() resolvedCounter.testGetResolvedCount()

Run it! If it produces no output, then the test was successful. (If you prefer a more explicit signal, you can print a "Successful!" message in the last line of test method.)

To understand what happens when the test fails, change the assert statement to this:

assert result == 2

Run it! It will fail and show you the actual result (1) as well:

Assertion failed: assert result == 2 | | 1 false

Cool, right?

When your script is complete and your tests are running fine, just comment out the invocation of the test methods and deploy the script back to Jira.

Running the unit tests in Jira

You may be curious, what happens if you don't comment out the test method invocation before deploying the script to Jira? It may even sound like a good idea to run the tests before each export.

Well, it would definitely work and the test failures would be written to the Jira system log. So far, so good.

But! Failed tests will also make the export itself fail: the assert statement will terminate the execution of the script and the PDF document rendering will stop. As the test failure details only appear in the Jira log, yours users (not looking at the log) will see only a broken PDF document with an unfriendly error message.

Therefore, running Groovy tests in Jira is recommended only for development purposes.

Debugging

You can efficiently develop most scripts using nothing else but the app's built-in editor, tracing and logging to write out variable values and see the control flow. Only when things get more complicated, you may want to use an actual debugger.

Debugging in the PDF template

You can use a simple technique to debug your export through the PDF template. It can be helpful both while developing it and also after it has been deployed to production.

The idea is introducing a boolean variable ${debug} to control if variable values are shown (debug time) or not (production time) in the exported PDF file. Here is an example of this approach:

#set($debug = false) ## set to true to display debug information

## ...

#if($debug)

<fo:block>DEBUG: number of issues: ${issues.size()}</fo:block>

#end

#foreach($issue in $issues)

#if($debug)

<fo:block>DEBUG: issue key: ${issue.key}</fo:block>

#end

<fo:block>$xmlutils.escape($issue.summary)</fo:block>

## ...

#end

The nicety here is that you can switch between the "debug" and "non-debug" modes easily even in a production Jira.

Debugging in the IDE

Well, Groovy scripts are just Groovy scripts. Those parts that are not tightly tied to Jira internals can be developed, tested and debugged using the testing approach in your favorite IDE.

As for Jira internals, you can use mock objects to simulate them. For example, in this sample script we used simple Groovy maps to mock Jira issues!

Debugging in Jira

After deploying your script to production, logging to the Jira log should be your primary tool to diagnose problems.

Logging

Logging from scripts

Logging from a script can be useful in a number of cases like writing debug information or signaling exceptional conditions with warnings. The app provides easy-to-use facilities to write to the log which can then be viewed via the web interface.

To write to the log from Groovy scripts, just use the logger "global" variable:

// used generally

logger.log("This log line was written by a Groovy script.")

// used typically in "catch" blocks (with a second exception argument)

logger.log("Some exception was thrown!", new IllegalStateException())

logger is available as a "global" variable. In order to access it within a class, you need to add it as a property to class and pass it as a constructor argument:

myTool = new MyTool(logger: logger)

class MyTool {

def logger

def foobar() {

logger.log("This log line was written from inside MyTool.")

}

}

If you don't actually use scripts, you can write to the log even from a Velocity template (cool, right?):

$logger.log("This log line was written by a Velocity template.")

To see the last 500 log lines (available for 30 minutes), login to Jira as admin, then go to Apps → Manage your apps → View Log.

Further reads

Recipes

Learn more about solving frequent customization needs with pre-tested recipes.

Troubleshooting

Learn more about finding the root cause of PDF export problems faster.

Next step

Read the recipes to learn useful patterns and tricks with Better PDF Exporter.

Questions?

Ask us any time.